Related Posts

The 1918 influenza pandemic: A global catastrophe

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed 50 million to 100 million people around the world. While infants and very young children and people older than 65 typically are most at risk of severe symptoms, complications and death from flu, the 1918 virus killed many young men and women in their prime, making it especially vicious.

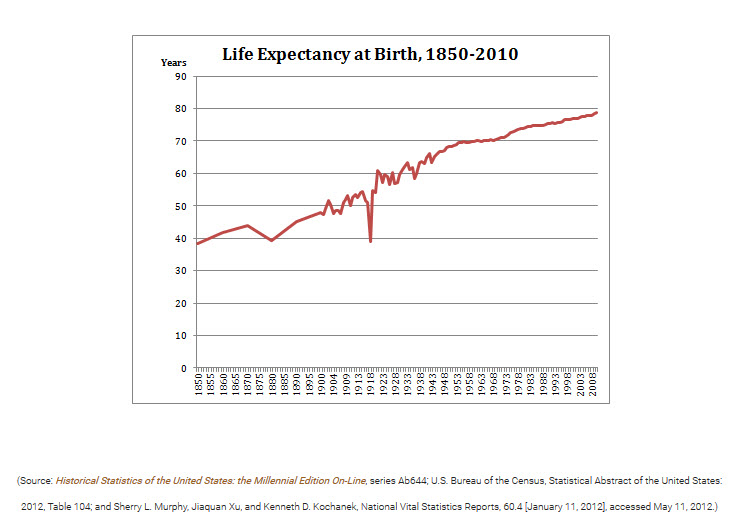

In 1918-1919, during the epidemic, more than 14,000 North Carolinians died, including UNC-Chapel Hill President Edward Kidder Graham, and his successor, M.H. Stacy, both in their early 40s. The pandemic was a defining event for the 20th century and, among other outcomes, was responsible for a 12-year decrease in life expectancy in the United States during that period.

Chart shows dramatic dip in life expectancy in 1918. Courtesy of Not Even Past.

Bookmarked between two eclipses, the pandemic happened quickly, first with relatively mild influenza in spring 1918, and then, with a vengeance, in the fall. The waves of illness came while WWI, which would claim 16 million lives, was raging in Europe. The virus thrived in overcrowded conditions on bases in the U.S. and tightly packed troop ships bound for Europe, and more soldiers died of influenza than on the battlefield. More people died in the 1918 pandemic than in World War I, World War II and other wars combined.

Of course, it wasn’t only soldiers who died. Entire families were stricken. American author Thomas Wolfe’s brother, Ben, died of influenza while Thomas was a student at UNC-Chapel Hill, and Thomas wrote achingly of the horrific death in his autobiographical novel, Look Homeward, Angel. The pandemic was a global tragedy on a scale we can barely imagine.

All this happened at a time when viruses were not understood, methods of prevention and intervention were primitive, people were given bad advice and many doctors had been deployed. In some cities, bodies were piled on porches because there was no more wood for coffins. There are stories of nurses and other brave volunteers who risked getting flu to take care of family members, friends and neighbors. There are also stories of children who starved to death after their parents died of flu – because no one wanted to venture near their houses. It was the worst of times.

Applying lessons learned from the past

In 1918, the world was unprepared to fight an enemy that vanquished the young and healthy. Today, the ease of global travel could make a pandemic faster and more furious. Many thoughtful people believe that it is not a question of whether, but when, there will be another pandemic.

As environmental historian Alfred Crosby, who died last month at age 87, wrote in America’s Forgotten Epidemic: The Influenza of 1918,

The world’s human population is more than three times greater than it was in the last year of World War I, which increases the likelihood of the spread of strains of any and all pathogens. The populations of the animals with which we exchange flu viruses, the source of epidemic strains, are vastly larger than they were in 1918. China, which tops the world in its number of humans, aquatic birds, and pigs, has been the source of many new flu strains since 1918 and will be again.

The health problems of our giant cities are especially daunting.

When an acquaintance who is a local bookseller and historian mentioned the centennial of the 1918 pandemic, I became fascinated by the topic – by the speed of the virus’s spread and impact, the devastation of communities, the particularly gruesome way in which people died as the virus invaded their bodies, and the fact that so little was talked about for so long. I was totally engrossed in the heroic stories of those who searched for, eventually found and recreated the virus so that it could be studied.

Crosby provided a painstaking summary of deaths from influenza in different parts of the world, along with other useful information in his book, which was first published in 1976 as Epidemic and Peace: 1918. I found a used edition of the book online and bought it in hard copy, something I had not done in a long time. When the book arrived, its inscription showed that it had been in the School of Public Health library at the University of Texas at Houston. Small world.

Much that is important about public health today occurred in the aftermath of the 1918 flu pandemic. Yet, most students are not aware of the connections between present and past, in relation to influenza. I did not know. I still wonder why it was forgotten and wonder whether there was a kind of global PTSD – that what people had seen was so horrible they could not speak of it, as was true for many who survived Hitler’s concentration camps. They wanted to put it behind them and move on, start over, leave the horrid past.

In addition to Crosby, Gina Kolata and John Barry also have written compelling, thoroughly engrossing books about the pandemic. When we decided to hold a symposium April 5-6 on the impact and implications of the 1918 pandemic, we invited Gina Kolata to give the keynote address. She gave a wonderful lecture based on her book, Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It.

On a recent trip to Asheville, my husband and I visited the gravesite of the Wolfe family and stood in front of Ben Wolfe’s grave. Later, I walked the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery and found the stone for M.H. Stacy and the graves of others who likely died of influenza. For some moments, time stopped, and I could have been back in 1918. Those few autumn and early winter months, especially, when sickness and death ravaged the world, were a time we must commit to prevent ever happening again.

Barbara