The statement below reflects my personal opinions and does not represent the position of the Gillings School of Global Public Health or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is longer than most of my Monday Morning posts – the topic is complex.

Related Posts

The Faculty Council resolves:

Developing and implementing any plan for the disposition of the Confederate statue shall include the following.

Faculty Council shall establish a committee of faculty who represent the diverse expertise and concerns of faculty in matters pertinent to the history and impacts of the statue. This committee shall be included by university administration in all planning for the disposition of the statue and related actions or developments.

The council should consider amending the resolution to include mention of including staff, students and people from relevant communities, even though they are not the council’s chief constituencies.

Background on the Chancellor’s recommendations

Last August 20th, protesters on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus (many not from campus) toppled the Jim Crow-era statue known as Silent Sam. At that time, I blogged about the Confederate monument as “an overseer of conditions that led to poor health” and expressed my passionate wish that, in place of Sam, “there be erected a statue of a person or group who furthered the causes of peace, equity and prevention.” I said that Silent Sam had no place on this university campus.

Since the toppling, there has been an almost constant drumbeat of activity around disposition of the statue.

The UNC Board of Governors (BOG) charged Chancellor Folt and the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees (BOT) to “present a lawful and lasting plan for the disposition and preservation of the Confederate monument commonly known as ‘Silent Sam.’”

At the BOT meeting Dec. 3rd, Chancellor Folt proposed, and the trustees approved, a plan to fulfill the BOG’s charge. (The BOG is expected to vote on the plan December 14th.. A vote in favor of the plan would be a next step toward getting the plan before the NC Historical Commission, which ultimately can grant or deny permission to move a statue or monument.) The plan states a strong preference to relocate the statue off campus. Noting the N.C. state law prohibiting this option, the plan proceeds with a fallback recommendation to construct a history and education center on the south side of campus in which to house the statue and contextualize our history.

Campus responses to the proposed plan

Many on campus and beyond are profoundly dissatisfied with the plan, including many students. Nevertheless, people around the state have different opinions, positive and negative, as do some people on campus. Reactions are strong on all sides and consensus is lacking on many important questions. Two of 13 BOT members, including UNC-Chapel Hill’s student body president, voted against the plan. Overall, our public health community is deeply unhappy with the recommendations, given our mission to eliminate inequities, our collective commitment to overcome racism and enhance diversity and inclusion in our environment and beyond, the efforts we have been making in the Gillings School to become more diverse and inclusive, and our history of standing against oppression. The presence of a Confederate statue on campus is at odds with that mission, as many of our students, staff and faculty have said. I agree with them.

A cross-campus strike was planned that would include, among other actions, withholding student grades until UNC leaders decide that the statue would not return.

I’m moved by the many courageous students and faculty, staff and others who have invested time, energy and passion, at personal risk, to advocate for the statue’s removal from campus, given historical and ongoing oppression it represents. Many have agonized, as I have, about how to support our university while raising legitimate questions about proper disposition of the statue.

While I believe that the statue should not return to campus, I disagree with the strike, an action that strategically and tactically misses the mark. As a student at the University of Michigan (UM), I participated in an 18-day Black Action Movement strike that led to an increase in Black student enrollment. I told a colleague about it recently, and he asked why that protest was different from the proposed strike at UNC. Robben Fleming, the UM president at the time, controlled many decisions at issue in that instance. Carol Folt does not. That’s why a campus strike is unlikely to affect desired outcomes and could engender significant backlash. If the goal is to remove the statue from campus permanently, then, strategies should be based on influencing decisionmakers. The chancellor is not the ultimate decisionmaker. A strike is not likely to influence the BOG or legislators.

Civil actions should be directed at the legislature and those who influence them. If the statue is to be moved, the law must be changed. The strike has great potential to harm students who may not know all the potential consequences that could ensue if grades are not recorded. No one knows.

Process and recommendations regarding the statue

While people may disagree with their recommendations, I believe that UNC-Chapel Hill leaders have acted in good faith. I have observed a team of people, including the chancellor, provost, chief counsel, vice chancellor for communications, vice chancellor for strategy and workforce development, and others (including members of the Faculty Executive Committee) trying to manage a process constrained from the start.

By the very nature of the charge given to them, they were straightjacketed, and they have worked around the clock to find a way out. Their charge required that any recommendations be lawful, which precluded moving the statue off campus unless various permissions were obtained. If the leadership team’s sheer will could have passed a law to relocate the statue off campus, such a law would have been passed.

However, this option was not within their control.

The leadership team also has been criticized for presenting a plan with only one recommendation.

The N.C. Museum of History in Raleigh is an ideal location for the statue, but achieving relocation to the museum would have been a much more complicated undertaking, due to legal and other constraints. We should continue pursuing this option.

Here is a relevant passage, verbatim, from the report:

Based on all we have learned from the thorough analysis of public safety and security, as well as by our analysis of feasibility and cost, our preference is to relocate the Artifacts [the statue and its accompanying plaques] to a secure off-campus location, such as but not limited to the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh…

This is the safest option that both preserves the statue and allows for its contextualization and public access…

While we acknowledge that relocation to an off-campus location such as a museum does not comply with the current law, our public safety concerns make it important for us to continue discussions concerning this avenue, even while moving forward with developing and seeking approval for an on-campus plan, which follows.

The chancellor and provost have been clear that they would prefer to move the statue off campus. I believe them. I agree that it has no place on our campus. Given the charge and the current law concerning relocation of monuments, a recommendation to move the statue off-campus would be deemed unacceptable by the trustees and board of governors.

(See recent FAQs for more information.)

Refusing to compromise on permanent removal of the statue from campus would be morally courageous. Then, the chancellor could accept her likely dismissal (as a result of this action), taking comfort in having done the right thing. Yet, one likely consequence of that act might be that the statue is returned to its McCorkle Place pedestal (which could happen regardless), the chancellor is gone, and we are at odds with her successor. Would we be better off? I do not believe so.

A decision about disposition of the statue is a classic rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma. Any proposal would be unacceptable to large numbers of stakeholders, and there are legal barriers to addressing, let alone persuading, the board of governors about the rightness of any course of action. (As a public university, we are funded by taxpayers, and the board of governors, elected by the North Carolina General Assembly, has a significant say in how dollars are spent across our University system.)

I infer that this left the chancellor and her team to recommend a decision that the board of governors might accept and yet would not return the statue to its original place at the gateway of the University. The result was the chancellor’s proposal and BOT’s approval of a plan that included several key recommendations, including building a history and education center at the periphery of campus to house the statue. The center, as the report emphasizes, also would be designed to convey the historical context for the statue and the University’s place in it.

How Silent Sam speaks to us

The statue is out of place and time. The world has changed dramatically in the century since its placement on campus in 1913. As was stated by Dr. Derrick Matthews, assistant professor of health behavior at the Gillings School, and others, the statue no longer belongs here, in a world in which we are striving for diversity, inclusion and equity, and where we still have so far to go to achieve these goals. The statue is a marker of a racist past when the rights of African-Americans were suppressed brutally.

Its presence today conveys that our institution continues to uphold and transmit those values. We do not.

“Silent Sam, like other memorials to the Confederacy, is a monument to treasonous rebellion against the United States, fought to preserve the enslavement of African-Americans,” wrote David Graham, in an August article in The Atlantic.

As I said last fall, I was moved by remarks made by Mayor Mitch Landrieu, of New Orleans, when Confederate statues were removed from that city in May 2017. He talked about the impact of the statues on minorities, especially African-Americans, who were reminded of the Jim Crow era and its aftermath each time they passed the monuments, every day.

Statues may be inanimate, but they evoke very real emotions. That’s a key point that many in our community are trying to make. The very presence of the statue causes pain.

This should be a place where students, faculty and staff members, and others feel safe, supported and free – from intimidation, fear and discrimination – to thrive. The constant reminder of one’s diminished status can be a social stressor that contributes to allostatic load (the long-term effects on the body of continued exposure to chronic stress), ill health and conditions such as high blood pressure. The ways African-Americans were treated historically, including during the Jim Crow era, left many with poorer health. The legacy persists.

A temple to white supremacy – or a history and education center?

Many in our community concluded that the proposed center would be a $5+ million temple to Silent Sam and the Confederacy. The money would be better spent on more important needs.

We should be clear that this is not a trade-off of one activity for another. Currently, the University does not have $5.3M to build the center. Funds would have to be raised or authorized by the legislature. That will take time.

Could a center be created that would not be a paean to the Confederacy? Maybe.

I have talked to people who say that we should forget the statue, and the Jim Crow era.

Under Jim Crow laws, oppressive segregation was institutionalized, even including public water fountains. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

I disagree. Each generation must confront – not sentimentalize – the past and learn from it. At the time I was growing up, many white Americans got a “whitewashed” view of history that ignored or minimized the profound suffering and generational inequities caused by slavery, Jim Crow, and continued structural and institutional racism. Many of my generation were not told the stories that have been handed down in African-American families.

I examined the websites of several museums dedicated to telling the truth about regrettable periods in history. Creating something powerful and authentic – a center that would allow us to analyze UNC’s and our state’s history in its full complexity – would need the deep engagement of campus faculty (especially historians), staff and students, and people external to the university, including people whose families experienced the Jim Crow era. It would require that we bring into the planning process as true partners people who have been targets of oppression and racism. As was true for planning the two museums noted below, those affected must be integral to the process at UNC. We would have to tell the story of how African Americans and other minorities have been treated and how they have experienced our university’s history over time. The campus never has dealt adequately with this history.

Consider the mission of the U.S. National Holocaust Museum – To advance and disseminate knowledge about this unprecedented tragedy; to preserve the memory of those who suffered; and to encourage its visitors to reflect upon the moral and spiritual questions raised by the events of the Holocaust as well as their own responsibilities as citizens of a democracy.

Similarly, the National Museum of African and American History and Culture tells the story of African-Americans in all its complexity. “This Museum will tell the American story through the lens of African-American history and culture,” said founding director Lonnie Burch, on the museum’s opening day. “This is America’s story, and this museum is for all Americans.”

Should we leave the Confederacy and the Jim Crow era behind? What will happen if future generations do not learn about Jim Crow, and how that time continues to shape the present? Won’t it make the past easier to repeat? Should we continue to turn a blind eye to ways the legacy of Jim Crow is all around us, even today?

The proposed UNC history and education center has been vilified by many, both on and off campus. Its greatest flaw is that it would house an artifact that causes pain by its very existence. As many have said, its proposed location also should be considered in light of minority students living in the area, nearby religious centers and a proximal veterans’ center. If it is the only way forward in the current era, then, the center should tell the unvarnished story of how this and many other universities (most, at the time, according to the book Ebony and Ivy) were built, including the story of an era many do not know about or would prefer to forget. It should contextualize the statue in an honest, accurate manner.

Contextualizing Silent Sam

While we wish for and even demand permanent removal of the statue from campus – it is not likely to happen now, despite our wishes and the costs of erecting a new building to house the statue. Yet, if the board of governors approves the plan, and that is still a big “if,” there is opportunity to use our history to shape our future.

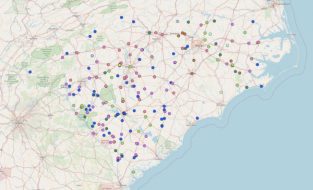

A recent article, published in UNC’s Endeavors, shows how powerful context can be. The article describes an ongoing class project undertaken by Dr. Seth Kotch, assistant professor in the American Studies department at UNC, about the suppressed history of lynching in the American South. Students engaged in this project, called A Red Record, have used news reports, oral histories and other sources to identify lynching sites across North and South Carolina from the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction to the 1950s.

Sites where people were murdered by lynching in the Carolinas are among those documented by UNC students in American Studies classes taught by Seth Kotch, PhD, assistant professor of digital humanities.

The maps provide a context that the statue on its pedestal fails to communicate. This context is granular, unvarnished, authentic. It brings out of the shadows – with specific names and places right here in Orange County and across North Carolina – the many human beings who, throughout the Jim Crow era, had no protection or recourse to law and justice, to basic rights we hold dear as Americans.

Many would say that society still is far from being equitable, and the Red Record project shows why this is so; it illustrates how the line from Jim Crow threads unbroken to the present and informs the work we must do today to cut that thread once and for all.

Yes, the statue should be removed, and then we could be done with it. So much time and money that could be spent on other activities – including addressing root causes of racism and inequity – is being spent on an artifact. Money should be invested elsewhere.

That likely won’t happen today. Many tactics, borne of righteous anger and a strong sense of justice, may make us feel better but will not achieve the goals. A strike will not eliminate inequities.

We are not helpless. Rather than strike, let us redirect strategy toward changing the hearts, minds and actions of those in control of these decisions. Better yet, let us work toward changing the law.

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice, Martin Luther King Jr.* once said. Let us shape the arc with the hammer of our votes, the weight of our consciences, and the power of our persistence. Justice will come.

— Barbara

*Attributed originally to the sermon “Of Justice and the Conscience,” by Theodore Parker, published in 1853, in Ten Sermons of Religion, a remarkable book.