In pursuit of an antiracist America

I ended the celebration of Black History Month with humility, realizing how much more I must learn — how much more most white people raised in the U.S., and educated, as I was, with a whitewashed history of our country, must learn.

Related Posts

America is a country I love, but it repeatedly has failed Black people from the time they were first brought to this country, in chains and shackles, against their will.

The story of this country is interwoven with the encroachment of structural racism into every aspect of American life, with insidious stealth and often brazen disregard for laws. We cannot walk away from the truth of what it has meant for millions of lives. Knowing is not enough. We must act for change.

Last month, when I read From Here to Equality by William Darity Jr., PhD, and Kirsten Mullen, I realized why reparations to descendants of slaves must be considered as a just policy.

At the Gillings School’s 42nd Annual Minority Health Conference last week, speakers, panelists and participants explored the theme of “Body and Soul: The past, present and future of health activism.” Keynote speaker Wizdom Powell, PhD, as tweeted out by health researcher Trenita Childers, PhD, urged listeners “to be convicted about what you want to accomplish and be brave; create an activism ecosystem so you’re not operating solo; be strategic; align yourself with other scholar activists.” There’s power in community, she reminded us.

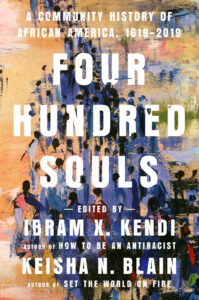

Four Hundred Souls

Ibram X. Kendi, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, who leads the Center for Anti-Racist Research at Boston University, and University of Pittsburgh historian Keisha N. Blain, PhD, concluded that the history of Black people in the U.S. only could be written by a community. They assembled 90 Black writers to tell the story of the 400 years since the first arrival of Black people who would be enslaved in this country. Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019, is an amazing book, sobering in its forthright presentation of the facts and the stories.

As a white person, I am ashamed. I am saddened, and I am repulsed by what white people systematically have done to Black people in this country over generations. While I am committed to do everything possible to contribute to a future where everyone thrives, the future is shaped by the past. I encourage you to read the book. Although we cannot undo the past, we can reckon with it and repair it to create a better future. Our Gillings School Inclusive Excellence Action Plan is an organic, evolving roadmap for a future without racism, where everyone thrives.

Read about Four Hundred Souls and Kendi’s responses to Boston University writer, Sara Rimer (yes, my sister), in BU Today, below.

BU’s Ibram X. Kendi Recruited 90 Writers to Tell Black America’s History

Poets, historians, journalists, philosophers, and activists were assigned a five-year period, from 1619 to 2019—and the book, Four Hundred Souls, took off

February 25, 2021

Ibram X. Kendi wanted to mark the 400th anniversary of the symbolic birthdate of Black America—August 20, 1619, when the first captive Africans were brought ashore in the colony of Virginia. Kendi, a leading antiracism scholar and the founding director of BU’s Center for Antiracist Research, thought about writing a book about that history, but decided there were already enough such books by lone male authors.

Ibram X. Kendi wanted to mark the 400th anniversary of the symbolic birthdate of Black America—August 20, 1619, when the first captive Africans were brought ashore in the colony of Virginia. Kendi, a leading antiracism scholar and the founding director of BU’s Center for Antiracist Research, thought about writing a book about that history, but decided there were already enough such books by lone male authors.

The story of those 400 years, from 1619 to 2019, is the story of a community and the only way to tell that story, Kendi determined, was with a community. So Kendi, together with University of Pittsburgh historian Keisha N. Blain, recruited 90 writers—historians, philosophers, journalists, anthropologists, activists, lawyers, novelists, and poets—and they all delivered.

The resulting anthology, Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 (One World, 2021), coedited by Kendi and Blain, is described as the first one-volume communal account of African American history—which is, of course, also American history. The book was published on February 2, and a week later, it debuted at No. 1 on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. The Root proclaimed Four Hundred Souls “a groundbreaking, epic, and deeply innovative exploration of how Black America as we now know it began” and “a love story to its descendants.”

“Collectively, this choir sings the chords of survival,” Kendi, the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history, writes in his introduction. “Of struggle, of success, of death, of life, of joy, of racism, of antiracism, of destruction—of America’s clearest chords, years after year, of liberty, justice, and democracy for all. Four hundred chords.”

BU Today spoke recently with Kendi about what he views as the significance of Four Hundred Souls and how it might be taught in school, why he and Blain chose to highlight stories of resistance to slavery, and how a book like Four Hundred Souls might have altered Kendi’s own views of Black people as a high school student.

BU Today: Why is this book important and who were you and Keisha Blain hoping to reach?

Kendi: First, it’s important for Americans to learn the full history of every single topic, and certainly of the Black American experience. But it’s difficult for any person to pull out a 1,000-page textbook, or even a single-authored book. And so we were thinking about a way to make a single-volume, 400-year history accessible to every single person and for every single American, who, I think, will be better served by understanding that history of Black Americans.

Can you talk about things in the book that were new and revelatory to you?

Read more here.