Related Posts

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkurl = "http://mondaymorning.web.unc.edu/2011/04/05/organizational-complexity/";

“A radical restructure is the only way to solve the systemic problems of the world’s biggest funder of biomedical research,” argues Michael M. Crow.

In a provocative article in Nature about the future of National Institutes of Health (NIH), Crowe suggests doing a thought experiment to redesign NIH in light of changes in science, medicine, public health, behavioral factors, economics, policy and a variety of other considerations.

Michael Crowe is President of Arizona State University and an out-of-the-box thinker. He proposes a reduction from 27 to three institutes. That’s probably not going to happen. He’s right that there’s been a proliferation of centers and institutes over the years. Some of them have resulted from intense advocacy. It’s getting harder to manage overlap, and there are significant administrative costs associated with every center/institute. I am a great fan of the NIH, having worked there and having been funded by NIH for most of my career. But like all our older institutions; if one were designing the structure today, it undoubtedly would look different. Three is too few, given the complexity of health issues. But 27 is probably too many. NIH director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, made the right decision when he recommended evolving National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) into the new National Center for Advancing Clinical Sciences. I say this although the activities NCRR funds are incredibly important.

As we grapple at UNC with a mandate to reduce organizational complexity, I’m sensitive to how difficult it is to change structures, and how many people find perfectly logical reasons not to change.

A doctor’s journey

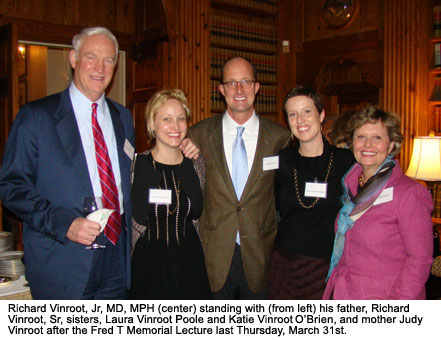

Over 400 people attended our William T. Foard Jr Memorial Lecture March 31st, and heard Richard Vinroot, Jr., MD, MPH give a passionate, sometimes hilarious, often poignant and fascinating talk titled “A Public Health Physician’s Journey Through Flood, Earthquake and the Wake of War.” He’s lived in one of the worst slums in Kenya, doctored through Hurricane Katrina and trucked throughout Haiti after the earthquake. Richard is not just a public health physician. He’s a public health hero!

Vinroot’s talk was about public health through the lens of a public health physician. His talk made me think a lot about what it means to be a public health doctor or a public health anything. People in public health used to make a distinction between medicine and public health. For a long time, Harvard’s website had a figure that showed public health on one side and medicine on the other. The traditional mantra was that medicine is focused on individuals and public health on communities. Thus, Hopkins’ slogan, “We save lives, millions at a time.” Having a population perspective doesn’t mean we only think about people in the aggregate. After all, what is a community but a collection of individuals? We added “individuals” to our mission statement, partly because we believe strongly that public health should not lose its connection to individuals. (Our mission is to improve public health, promote individual well-being, and eliminate health disparities across North Carolina and around the world.)

Looking at medicine through the lens of public health means that when Dr. Vinroot sees a homeless person under a bridge, he understands that there are root causes that may affect the person being homeless. Unless those are changed, he will stay homeless. The homeless man is a human being with needs, but from a public health perspective, he also represents a group of people with significant health threats. It’s the social ecological framework perspective and that’s at the heart of public health. (See IOM’s report: Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?)

Happy Monday. Barbara