What I learned from Barry Blumberg, MD, PhD

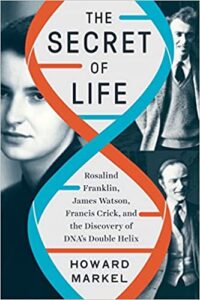

The motivation to write this post came as I finished the book, “The Secret of Life,” by Howard Markel, MD, PhD, the George E. Wantz Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. It’s an engaging book about the race to discover the structure of DNA.

Related Posts

I’d recently read the 1975 biography of the brilliant chemist and X-ray crystallographer, Dr. Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958), by Anne Sayre. I have been captivated by Franklin’s extraordinary work, the tragedy of a life cut brutally short by cancer, her experience of antisemitism from scientists who believed dogma about Jewish people, and the misogyny and dishonesty with which she was treated in what was unapologetically a man’s world. Like Franklin, early in my career, I often was the only woman in a meeting, and I still recall some of the belittling comments that were made toward me.

Markel, an outstanding historian of medicine, tells the behind-the-scenes story of the race that involved many scientists, three of whom — Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins — went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Markel recounts how the drive to be first (and to win the Nobel Prize) led to deception in getting access to Franklin’s data and to her ostracism. Both Markel and Sayre, who was a friend of Franklin’s, described the bigotry Franklin experienced, including the way male colleagues shunned her, prevented her from joining in events critical to collaboration (such as lab lunches), and ultimately colluded in sharing a photograph of the molecular structure of DNA she had created — Wilkins showed it to Watson and then shared with Crick — without her permission.

Markel, an outstanding historian of medicine, tells the behind-the-scenes story of the race that involved many scientists, three of whom — Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins — went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Markel recounts how the drive to be first (and to win the Nobel Prize) led to deception in getting access to Franklin’s data and to her ostracism. Both Markel and Sayre, who was a friend of Franklin’s, described the bigotry Franklin experienced, including the way male colleagues shunned her, prevented her from joining in events critical to collaboration (such as lab lunches), and ultimately colluded in sharing a photograph of the molecular structure of DNA she had created — Wilkins showed it to Watson and then shared with Crick — without her permission.

Sadly, Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958 at age 37. Her death certificate noted that she was a spinster, a fact that we now would consider irrelevant. Watson’s failure to recognize her contributions, even after her death, is unforgivable. His antisemitism and racism were among the reasons he was stripped of his position as chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 2007. That was as it should be.

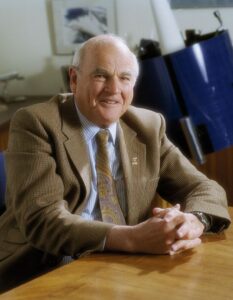

Thinking about the protagonists in Markel’s book prompted memories of my early career as a researcher at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Fox Chase had a great tradition of bringing people together from across the institution every day for tea (thanks to a donor). Basic scientists would come in their shorts, clinicians in their white coats, and population scientists, like me, in our street clothes. I got to know Baruch S. Blumberg, MD, PhD, who, in 1976, had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the hepatitis B virus and his work to develop a vaccine against it. FCCC had a large program that involved inoculating children in families attending Korean churches in the Philadelphia area on Sundays. I sometimes volunteered to help.

Blumberg — Barry to all — was a generous, exuberant scientist who mentored many researchers over the years, with fairness and concern for them as people. I was invited to a walk on the Delaware Canal towpath (which runs almost 60 miles) with Blumberg and about five others one Saturday in the mid-1980s. It was one of those life-altering events. I cannot recall exactly how far we planned to walk, but I think it was about 15 miles. It was a beautiful fall day, and we started out with Barry talking about the plants we saw along the way. You’d have thought he was a botanist from his extensive knowledge of flora and fauna.

As we walked, we also talked about how science is done, and how it had changed in his lifetime. (He must have been in his mid-50s at the time.) He said he thought people were going to too many scientific meetings and not taking enough time to think about their research. I’ve always taken that to heart and regularly ask myself, “Is my job to go to meetings and talk about my work or to do the work?” Obviously, we must do some of both, but if it tilts too far one way or the other, there’s imbalance.

Then, I recall spending hours talking about lab notebooks and the importance of meticulous recording of one’s work and observations. We also discussed ethical issues in cancer research. This was before computers were used for much of the recording process. I asked him about what he recorded, and how it helped his thinking. It was a fascinating look inside the mind of a great scientist and researcher. I’d been keeping notebooks, but after that conversation, I became much more consistent about it. Alas, I lacked Blumberg’s drawing ability and his brilliance. I used to sometimes pay attention to his drawings and doodles in meetings. They were amazing.

As we reached various points along the path, we asked one another if we should turn around and head back, and each time, we said no, let’s keep going. When we had matched marathon distance, 26.2 miles, we decided to stop for a celebratory dinner. (We’d left a couple of cars there, thinking we’d be driving from an earlier point along the canal.)

As we reached various points along the path, we asked one another if we should turn around and head back, and each time, we said no, let’s keep going. When we had matched marathon distance, 26.2 miles, we decided to stop for a celebratory dinner. (We’d left a couple of cars there, thinking we’d be driving from an earlier point along the canal.)

In Blumberg’s obituary, Annie Westcott, leader of an organization for youth that she and he had founded together, said,

…a walk with Barry Blumberg was always an education. ‘It was like going to the best documentary or lecture that you’ve ever had in your whole life,’ she said. ‘He knew everything about everything.’

That’s it. He seemed to know everything about everything! I’ve often thought about Blumberg’s generosity in sharing his wisdom and time with several junior colleagues that day. In contrast to Watson, Blumberg had a huge heart for sharing, and when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, 17 colleagues traveled with him to Sweden.

It was a different time and place when we took that walk along the Delaware Canal. I don’t even know if the types of events we enjoyed could occur today. I learned so much about science, conducting research with integrity, the intersection of different sciences and the sheer joy of discovery. I came to think about my time as an even more precious resource that should not be squandered. The day had one other benefit: it gave me the confidence to train for the NYC marathon, which my husband and I completed a few years later.

Barbara