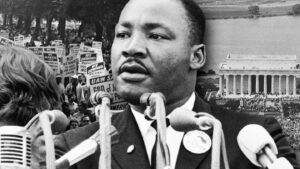

Rev. Dr. King’s continued impact

Martin Luther King Jr. had a huge impact on me and my generation. He was a hero, and his death was a tragedy.

Related Posts

In April 1968, when Dr. King was assassinated, I was a college student living with my then-boyfriend’s family in the Detroit suburbs before departing for a waitressing job in Wisconsin. The night Dr. King was murdered, and for several nights after, we could see the smoke rising up from multiple places in the city as it burned. The scene was repeated in scores of cities across the United States. Anger burned and simmered everywhere, and everything was on the line that spring and summer.

In an article published Jan. 17 in The New Yorker, Jelani Cobb wrote,

In an article published Jan. 17 in The New Yorker, Jelani Cobb wrote,

This holiday honoring Martin Luther King, Jr., sees a nation embroiled in conflicts that would have looked numbingly familiar to him. As school curricula and online discourse threaten to narrow our understanding of both past and future, it’s more important than ever to take stock of our history and its consequences, as King did in his speech more than half a century ago [March 25, 1965, on the grounds of the Alabama state capitol]. In Montgomery, the civil-rights leader spoke of the intransigent optimism that had led activists to fight for change, in the face of skepticism about what could actually be achieved.

The fight for justice and equity continues in the U.S. and on our campus. Today, the very voting rights for which Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and others fought are imperiled across the U.S. It is not a time to give up or lose hope. Intransigent optimism is needed today just as in 1965.

For the past year, I have served on two different university committees, one to consider names recommended for removal from university buildings and another to recommend names to replace those removed. Data come from reports of the University Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward, led by UNC-Chapel Hill professors James Leloudis and Patricia Parker. It has been a life-altering experience for me.

I knew far too little about the real American history even though I minored in American Studies in college. The history of this country that I and most of my generation were taught did not include an honest assessment of how Black people for centuries were brought here as slaves, in chains, nor how local, state and federal policies and laws from the post-Civil War period in the U.S., through the early 20th century and later, systematically discriminated against Black Americans. The words Jim Crow never conveyed the terrible reality of the crimes against minorities nor use of the law to hold them back. Far too often, racist state and local laws were passed for one purpose only: to discriminate against Black people.

Some of the men whose names are on our buildings were followers of Jim Crow tenets; others were leaders who acted boldly and often cruelly to keep governance of North Carolina in the hands of white men and preserve institutions, including UNC-Chapel Hill, as provinces of white males. One of the men, Charles Brantley Aycock, class of 1880, “condoned the use of violence to terrorize black voters and their white allies; campaigned for governor in 1900 on a platform of white supremacy and black disenfranchisement; and embraced ‘White supremacy and Its Perpetuation’ as the guiding principle of his political career.” (See Resolution 001) His name has been removed.

Hortense McClinton, 103, and family members of Henry Owl joined the Chancellor and other Carolina community members in a small virtual gathering last month to mark the renaming of McClinton Residence Hall and the Henry Owl Building.

Some of the names chosen to replace those removed from buildings reflect the sons [and daughters] of former slaves about whom King spoke. (Publicly available on the University Commission on History, Race, and a Way Forward web site.) As we read about their lives, I was overwhelmed by their pain and misery, the unfairness of the world in which they lived—in Chapel Hill and far from it.

Dr. King imagined a country in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” To do that, we must confront our shared history and find, as the UNC Commission’s name reflects, a way forward. We can do that by coming as close as possible to standing in the shoes of those who came before us, with empathy, and act to right wrongs. We must admit that even those of us who are well-meaning have sometimes been perpetrators. It is not sufficient to confront our history, but it is necessary.

We learn what we are taught. I was brought up believing in the good of the GI Bill that allowed my parents, who grew up with little, to buy an affordable house after my father’s service in WWII. We did not know that some former soldiers were denied the right to affordable home loans, setting in place inequities that persist and grow with each generation. It was not until I took the Racial Equity Institute Groundwater Training that I read legislation, followed families and saw the long legacy of inequity. White middle-class families like mine, who might never have become homeowners, benefited from the GI Bill. For too many Black veterans, their only legacy was the challenge of overcoming inequity. We should study history, learn its lessons and right its wrongs.

Martin Luther King Jr. understood that freedom without economic mobility is hollow. His speeches presaged many of the pillars of recent legislation, not just voting rights but economic (e.g., a living wage, childcare support) and educational ones (such as free community college), as well. Unfortunately, much of that legislation was rejected, but it should be revisited. We should remember the man, Martin Luther King Jr., and all he stood for, and recommit to action to achieve the still-unrealized dream.

Martin Luther King Jr. understood that freedom without economic mobility is hollow. His speeches presaged many of the pillars of recent legislation, not just voting rights but economic (e.g., a living wage, childcare support) and educational ones (such as free community college), as well. Unfortunately, much of that legislation was rejected, but it should be revisited. We should remember the man, Martin Luther King Jr., and all he stood for, and recommit to action to achieve the still-unrealized dream.

Barbara

Banner image: Martin Luther King Jr. Bridge at dawn (St. Louis); CC-BY-2.0