Black Lives Still Matter

The past week has been profoundly sad, and the pain continues. Still in the throes of a global pandemic, we are sickened, angry and traumatized by repeated acts of violence against Black people, particularly Black men, in the United States.

Related Posts

Many of our Black faculty and staff members and students are feeling despair and exhaustion. We have seen a horrifying video of a Black man named George Floyd dying at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis, lying on the ground with a white policeman’s knee on his neck as he cried that he was unable to breathe and was going to die. Before George Floyd, there was Ahmaud Arbery, killed Feb. 23, as he was jogging, by several white men in Georgia intent on vigilante justice. It took months – and a viral video — before arrests were made. Women have not been spared. We remember Breonna Taylor, an emergency medical technician in Louisville, Kentucky, shot in her apartment by police March 13th, apparently a case of mistaken identity.

Floyd, Arbery and Taylor are some of the most recent victims in a litany of unjust killings of Black people in America that has continued for more than 400 years. Citing an article in The Conversation by Connie Hassett-Walker, a professor of criminal justice at Kean University in New Jersey, in a New York Times column, Spencer Bokat-Lindell wrote:

In the South, policing evolved from slave patrols, white vigilantes who enforced slavery laws; in the North, it emerged as a way to control a ‘dangerous underclass’ that included African-Americans, Native Americans, immigrants and the poor. ‘Policing’s institutional racism of decades and centuries ago still matters because policing culture has not changed as much as it could,’ she writes in The Conversation. ‘The roots of racism in American policing — first planted centuries ago — have not yet been fully purged.’

I write on behalf of many at the Gillings School of Global Public Health who condemn the harassment, terrorizing and killing of Black men and women and other minorities in communities across this country, including but not only by police officers. In saying this, we recognize that most police officers do not injure or kill unarmed civilians. (New York Times analyses show the numbers of reported police killings of civilians have changed little in recent years. However, reporting to the national database of fatal and non-fatal incidents involving police use of force is voluntary and not required, which complicates data gathering.)

Law enforcement violence is a public health issue and a visible, abhorrent symptom of the racism that still marks too many facets of modern American society. Like a virus, racism is insidious and can damage everything it infiltrates. Racist practices are at odds with police codes of conduct. For example, the section of the Minneapolis Police Department code of conduct on “use of force” says that officers are required to intervene when they witness something that is wrong:

It shall be the duty of every sworn employee present at any scene where physical force is being applied to either stop or attempt to stop another sworn employee when force is being inappropriately applied or is no longer required.

No one stopped the killing of George Floyd. And while it is important for justice that video footage was captured, what if some of those people who were present had physically tried to stop what was happening? How would things have ended? What if one of the police officers had the courage and integrity to stop the killing?

Racism is a public health crisis

Andrea Jenkins, a Minneapolis City Council member, in speaking to the city she loves, called the racism that killed George Floyd a public health issue that should be considered a state of emergency. She also decried the violence happening in her city and said it was not the way to deal with the problem of racism, a disease, a virus that has infected America for 400 years. She began by singing Amazing Grace and ended by quoting Leroy Williams, a man at the scene who said, “We gotta make a change, brother.” We gotta make a change, brothers and sisters.

I agree with Councilor Jenkins. I also agree with the recent American Public Health Association (APHA) statement that said, “Racism attacks people’s physical and mental health. And racism is an ongoing public health crisis that needs our attention now!” Our country’s long history of racism has caused Blacks and other minorities to experience shorter lifespans and more sickness than their white counterparts; to suffer chronic conditions younger and at a rate not seen in others of similar ages; often to be diagnosed at later stages with diseases like cancer, when the likelihood of cure is much less.

While education is both an equalizer and a major predictor of health status, Black men, especially, are less likely to finish high school and college, in large part, because of our profoundly and systemically unequal education systems, and then they receive lower pay and work in lower paid jobs. According to a 2019 study by EdBuild, non-white school districts each school year get $23 billion less than white districts, despite serving the same number of students. That is an average of $2,226 less per student. The pandemic has shone a spotlight on these inequities, since people working in lower wage, service-sector jobs are more likely to die of COVID-19.

In the past four years, minorities have fallen behind on many measures of health and well-being. Millions lost health insurance they had gained under the Affordable Care Act. Now, at least 20 percent of Americans say they cannot afford prescription drugs they need, with higher rates among minorities. And when COVID-19 pummeled the country, it hit minority communities harder than white communities, although no group has been spared. As a risk factor for worse health and health outcomes, it is not a good time to be minority in America. It is especially risky to be a Black male. Truthfully, it has never been a good time to be a minority in America. That these conditions continue in 2020 should galvanize us all. We can, and we must, do better.

What are we going to do about it?

We must look both inward and outward. In looking outward, every person of voting age should evaluate how things are working in this country. Are we fair, just, and is this a place where every child grows up with the capacity to achieve their potential? Vote your conscience on November 3. Pay close attention to local and national elections. Give what you can to candidates who reflect your values and work for candidates you support. Get out the vote. Push for change where you live, learn, work, play and pray. Together, we can make a difference.

We will continue to pay attention to and work to change the root causes of poor health in communities through our teaching, research and practice. One example: a group of Gillings School students and faculty members in Environmental Sciences and Engineering partnered with a community in Apex, N.C., helping to supply the data that compelled City Council to agree to provide city water to a mostly Black community there. We can continue to use our scholarship for the public good, one of the pillars of Carolina Next, the UNC-Chapel Hill strategic plan.

We can complete the 2020 U.S. Census, by October 31 at the latest, and encourage others to do so, especially members of racial and ethnic minority groups, who historically have been undercounted in previous censuses. The allocation of roughly $1.5 trillion in federal funding – including support for critical public services like hospitals and health care clinics, schools, roads and emergency response — is informed by census data collected once every 10 years, as are countless research projects and the number of elected representatives each state has in Congress. (See “Why Some Americans Don’t Trust the Census,” by Jessica Sanford, of Carolina Demography.)

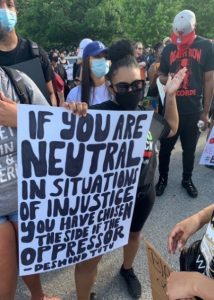

This is a time for boldness. We will not be bystanders. If we see injustice, we will speak up and stand up. Some minority students have experienced microaggressions in class, both from instructors and other students. What if another student or an instructor spoke up and said it was not right? So often, people feel embarrassed, even angry, but feel helpless and afraid to speak. What if someone other than the victim calls it out, sharing the burden?

We can join the many thousands of people around the country and world who are demonstrating for justice, equity and an end to racism. (See the American Civil Liberties Union’s guidance on “Rights of Protesters” and “How to Protest in a Pandemic.”)

We will continue to host the Minority Health Conference and the webinar series, Emergency Preparedness, Ethics and Equity, to offer a public forum for voicing critical issues.

We will look inward. If we grew up white, we are privileged, even those of us who came from families, like mine, without a lot of means.

We will listen to the lived experiences of the people around us. While people who are not Black cannot know what it is like to walk in the shoes of a Black person in this country, we can try to understand. When one of our colleagues told a group that she worries every night whether her husband will make it home safely because of the potential for any Black man to die at the hands of police, it changed how I and others think about safety. We felt viscerally how her life is different from ours. It is not fair that she should live with constant fear for her husband and son.

Those who are white, as I am, can take steps to educate ourselves on being effective, action-oriented, accountable allies (see “Black People Need Stronger White Allies — Here’s How You Can Be One”). As several of our students said, “We can also share resources about the ways that non-Black people can show up for our Black classmates.”

We will have the humility to admit that no matter how well-intentioned we are, no matter how deeply we want change and have tried to effect change, we have not moved fast enough or far enough. Therefore, we, too, are part of the problem. We will examine our own prejudices, biases and blind spots; we all have them. The Racial Equity Institute (REI) “Groundwater Approach to Racial Equity” program offers one effective way to do this. We are hosting four training sessions in June. I plan to participate. Please join me.

We can do better. I can do better. Together, we will do better.

Barbara

Update: To be consistent with and amplify language used in statements by the American Public Health Association and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health, the word “emergency” has been replaced with “crisis” in the title and text of this post.

Comments

[…] Dean Rimer talks about a parallel pandemic of racism in America that’s playing out alongside the coronavirus. You […]

The Pivot: Mya Roberson - UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health