Related Posts

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkurl = "http://mondaymorning.web.unc.edu/2010/11/29/global-universities/";

Being a global university

Wildavsky’s premises

I just finished Ben Wildavsky’s 2010 book, The Great Brain Race: How Global Universities Are Reshaping the World. His thesis is that the global academic order is transforming in far-reaching ways (p.3), and that free trade in minds (p.5) is a fundamental part of that change. He describes intense global competition (partly reflected in rankings races) for the best students and faculty around the world as more than 3 million students each year seek education outside their own countries. Foreign enrollment in other countries is growing even faster than in the U.S. Wildavsky argues that as economies improve, “more and more people will have the chance, slowly but surely, to advance based on what they know rather than who they are” (p.5).

The quest for global presence, reputation, even domination, is driven by a variety of forces, including recognition that in a global universe, we must have global knowledge, students, faculty and influence. Global leadership is part of overall leadership, reputation, and brand. Health and economic well-being are related directly to education. In public health, of course, some of the greatest challenges are found in developing countries. If we want to solve problems, we must go where the problems are.

Some universities have created global physical campuses in places like those in Doha, Abu Dhabi and Singapore—there are now more than 165 of them. Others have focused on designing and delivering virtual programs, often in partnerships with universities within countries. The same is true for schools of public health. Some universities have decamped from their ambitious plans for far-flung campuses, and there are some cautionary tales in their sagas. Over time, Wildavsky predicted more global activity, more consortia and organized global efforts by universities in partnerships with one another.

Global schools of public health and the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health

What it means to be a global school of public health is an evolving definition, with an ever-rising bar. What it might have meant 70 years ago is a long way from what it means today. Then, it might have focused on students and faculty moving back and forth between various countries as our faculty did when this School began in 1939. Today’s notions are more nuanced. Being global is partly attitudinal, a frame of mind and way of looking outward, viewing us all as global citizens. That’s how the majority of our students see themselves. It also should involve real presence in other countries, not just token visits. There could be a physical campus. That is not a necessity as long as there is connectivity. Shared, organized research and teaching programs (Our Executive DrPH program now has organized a global consortium of similar programs.), a critical mass of faculty and students engaged in two way traffic between countries, appropriate course content (We’ve globalized our content and created a global health certificate, now online.), paid global internships and field placements and strategic, global partnerships seem inherent in the concept of a global school or university. That means sufficient resources, including in communications, devoted to global reach and activities to achieve recognition for a school or university’s global-ness.

What it means to be a global school of public health is an evolving definition, with an ever-rising bar. What it might have meant 70 years ago is a long way from what it means today. Then, it might have focused on students and faculty moving back and forth between various countries as our faculty did when this School began in 1939. Today’s notions are more nuanced. Being global is partly attitudinal, a frame of mind and way of looking outward, viewing us all as global citizens. That’s how the majority of our students see themselves. It also should involve real presence in other countries, not just token visits. There could be a physical campus. That is not a necessity as long as there is connectivity. Shared, organized research and teaching programs (Our Executive DrPH program now has organized a global consortium of similar programs.), a critical mass of faculty and students engaged in two way traffic between countries, appropriate course content (We’ve globalized our content and created a global health certificate, now online.), paid global internships and field placements and strategic, global partnerships seem inherent in the concept of a global school or university. That means sufficient resources, including in communications, devoted to global reach and activities to achieve recognition for a school or university’s global-ness.

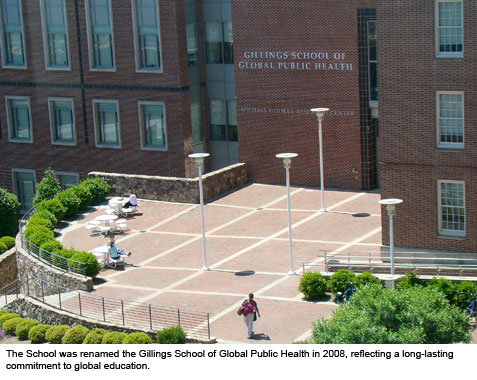

We added global to the School’s name in 2008 to reflect the fact that we have been a global school since our beginning in 1939. Our views of what it means to be global and how that relates to local have evolved over the years, and I expect them to continue to evolve. One thing is clear: we must continue to be an outstanding global AND local school. We’re not turning back.